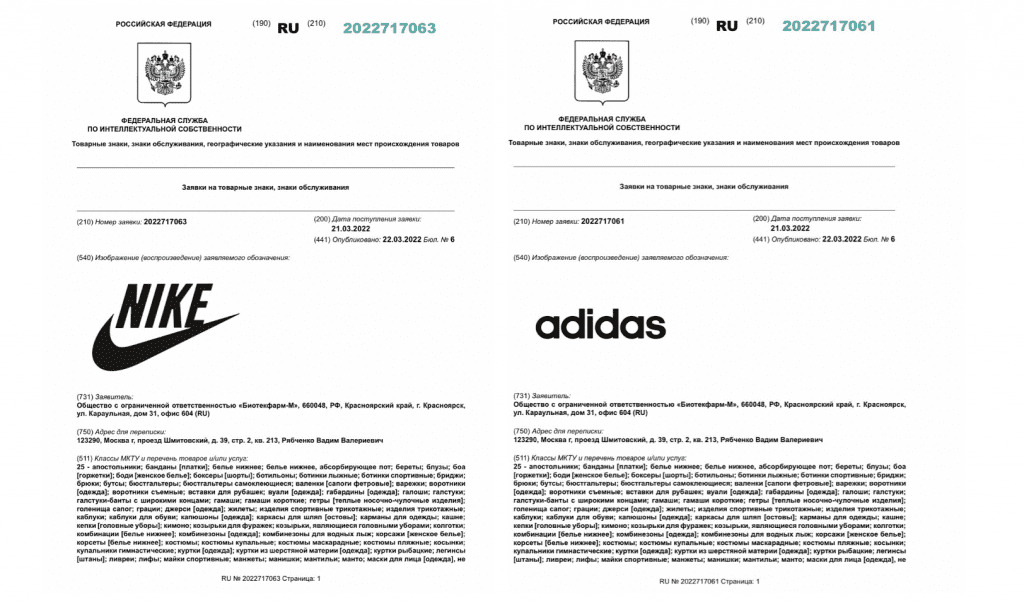

Christian Dior, Chanel, and Givenchy are not the only brands being targeted by an influx of trademark applications in Russia. Nike, adidas, Puma, Levi’s, BMW, and Audi have joined a growing list of Western titans falling prey to bad faith filings, as varying sanctions, widespread logistics/supply disruptions, and intense pressure from stakeholders have prompted most retail companies to temporarily halt their operations in Russia. At the same time, reports that the Russian government is considering putting a moratorium on trademark protections for companies in “unfriendly” countries and talk that the country’s Ministry of Economic Development will allow for the free flow of grey market goods is forcing companies to consider both the immediate and long-term implications for their valuable brands.

One of the immediate results of the exodus of Western brands from the Russian market has been an “unprecedented amount of [unauthorized trademark] filings,” targeting companies that range from Audi to adidas, Moscow-based intellectual property lawyer Ana Skovpen tells TFL. While the Federal Service for Intellectual Property in Russia – commonly known as Rospatent – has faced similar filings in the past and “refused such applications without interference from the [non-native] rights holders,” she states that the volume of “abusive” filings is significantly greater now, and trademark practitioners and brands, alike, are “not sure how Rospatent will examine these applications” in the wake of the war and Western sanctions.

The Wild West for Trademarks in Russia

Skovpen says that she does not believes that Rospatent will “spontaneously ignore all regulations and case law” and register these obviously-opportunistic trademark applications across the board. The recent decision of a Russian court to toss out a trademark and copyright case against a Russian individual over his infringement of popular cartoon character Peppa Pig, citing American and British sanctions as a basis for refusing to recognize Peppa Pig-owner Entertainment One’s rights, was, in fact, “a surprise,” Skovpen says. However, she is skeptical that heavily-criticized decision will prove to be the norm when it comes to how trademarks will be treated in Russia going forward. (Entertainment One is headquartered in the United Kingdom, and was acquired by U.S.-based Hasbro following the start of the lawsuit.)

In the event that bad-faith filings, such as those filed for Chanel, Dior, Levi’s, etc., are, in fact, widely registered by the Russian intellectual property office, what can brands expect? In a worst-case-scenario, the effect could be far-reaching. Should such hypothetical registrations come intro fruition, the targeted companies “may expect an array of fraudulent actions” to follow, Skovpen asserts, such as “the subsequent registration of similar domain names, and the creation of similar websites and social media accounts,” along with a rise in “parallel trade (imports) of their products and counterfeiting.”

If such a situation were to come into play, it would be “a wild west,” Skovpen says, and it certainly “would be challenging – or even possible – for brands to return” to the Russian market.

Echoing this sentiment, Caldwell Intellectual Property Law attorney Julie Tolek states that “the unpredictability of the future for enforcement of intellectual property in Russia makes it difficult for “brands from ‘unfriendly countries’” to anticipate what a return to the Russian market might look like. It certainly is easy to imagine the possibility that the parties currently seeking to co-opt famous’ companies’ trademark by way of fraudulent applications may “hold those marks/brands hostage and extort the non-native brands with a licensing agreement in order to use their own marks in Russia again.”

Tolek notes, of course, that if these “Russian spin-off trademarks are, indeed, allowed registration, and the [bona fide rights holders’] current registrations in Russia are not cancelled but rather, merely go unenforced, the more recent trademarks would, technically, have a later priority date than those original, valid marks.” If this scenario were to occur in the U.S., she states that “the first mark would have priority rights over the second mark,” and thus, the bona fide rights holders “would have the ability to file a cancellation of the spin-off/infringing marks.” This could be a potential course of action for companies if/when they opt to re-enter the Russian market.

And speaking of cancellations, in the event that such bad-faith marks are registered, Skovpen says that because at least some of the applications are being lodged purely as a way to gain registrations (Russia is a first-to-file jurisdiction) and not because the filing party “actual intends to use the mark,” Western brand owners may be able to “aim for cancellations on non-use grounds if the trademark owner does not use trademarks for three consecutive years.”

A Market for Fakes?

As for the immediate future, an increase in counterfeits and/or grey market goods is expected, as the Russian government explores ways to make up for the overarching loss of goods, including in the retail space. In some sense, Tolek contends that brands like McDonald’s, which was one of the first to be targeted by bad faith filings, may not face much damage, as counterfeiters might face an uphill battle that goes beyond merely registering a trademark should they actually want to compete. “They need to do more than just register a name – they need the trade secret recipes that make McDonald’s, McDonald’s,” she says. “If these knock-off McDonald’s in Russia are just selling plain burgers that you could grill yourself, the value of these knock-off trademarks is somewhat questionable.”

The same rings true for luxury brands. “Many consumers are not merely looking for the prestige of a brand name or logo” when they purchase luxury garments and accessories, per Tolek. They also seek “the quality and artisanship that goes into these luxury items – the details that make them coveted investment pieces.” With this in mind, the consumers that were buying up the bulk of luxury goods in the Russian market prior to the onset of the war and corresponding sanctions may not be easily tempted by sub-par copycat offerings.

Should the luxury knockoffs “fail to deliver on this higher standard, any perceived value of the spin-off trademarks will likely also fizzle out,” according to Tolek, “just like the knock-off McDonald’s.”

And practically speaking, it is worth noting that the potential for luxury brands to suffer the ill-effects of a surge in counterfeits in the Russian market may be dimmed by the fact that no shortage of their most loyal clients (i.e., the deep-pocketed, multiple passport-holding Russian oligarchs) are accustomed to – and may have already resumed – shopping for the bulk of their luxury goods purchases in markets outside of Russia, such as Dubai. As the Guardian reported this weekend, the richest Russians have fled the country, with many seeking refuge in luxury havens like Dubai, where “the oligarchs and other cashed-up Russians and their riches are welcome,” as the UAE has “not followed western governments in using sanctions as retaliation for the invasion of Ukraine.”

THE BOTTOM LINE: Ultimately, no matter where brands stand on the spectrum of competition/damage from a rise in counterfeits, the reality is that uncertainty abounds, and Skovpen says that there is nary a foreign company that does not “fear nationalization, trademark and domain squatting, and a lack of protection” for their valuable trademarks in Russia.