[ad_1]

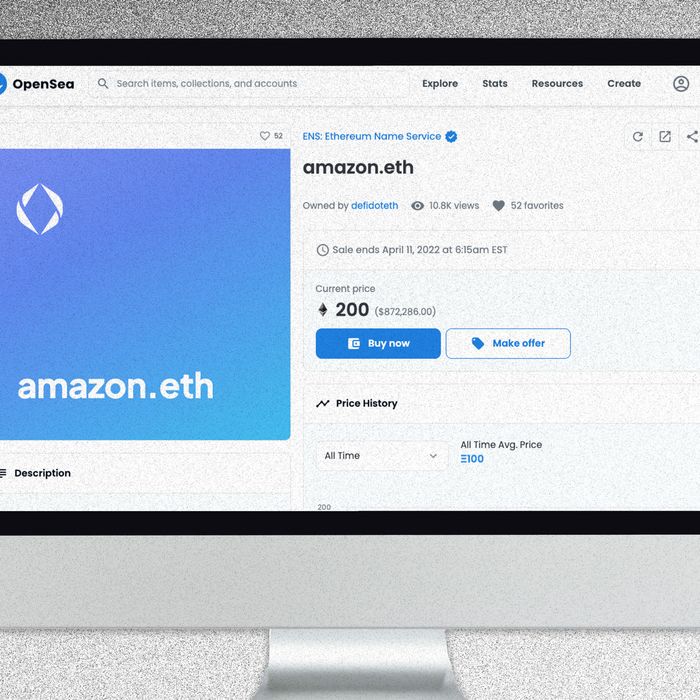

A lot of people are suddenly betting that, in the metaverse, .eth addresses will be the new .com. So what is amazon.eth worth?

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer;

When NFTs first came into the public consciousness, the whole idea behind them was a little weird. Here were these crypto certificates of ownership attached to pictures of bored apes or videos of Kevin Durant on the court, but they didn’t give anyone the copyright to those specific media. Nevertheless, they took off, with tens of thousands being traded every day. Now, there is a new object of hype in the crypto world: .eth domain names, an address for people to use exclusively on a crypto-based internet out of the reach of your typical browser. (Perhaps not coincidentally, they are related to NFTs; the domains can be used as a place to show off one’s crypto holdings.) The race to acquire Ethereum Name Service domains is reminiscent, if on a smaller scale, of the one for .com names in the early days of the internet. Many buyers are trying to snap up as many prime addresses as possible, hoping to resell them for a lot more money.

This month alone, more than 71,000 domains have been newly minted on the Ethereum Name Service — its biggest month ever, going back to 2017. The buying rush has created thousands of new potential digital landlords — some of whom have collected hundreds of domains. The bump has been helped by Silicon Valley celebrities like Balaji Srinivasan and actual celebrities like Ashton Kutcher, who have both taken to Twitter to promote the domains. At OpenSea, a large NFT marketplace, amazon.eth is currently for sale for nearly $1 million, while Nike.eth is listed for more than $4 million. Recent sales include adele.eth for around $6,000, radiologist.eth for $4,000, and boy.eth for $65,000. On Discord, the chat app that’s preferred among the gaming and crypto communities, an ENS domain server is flooded with people trying to unload bundles of less impressive names, like pussylord.eth for about $200 before transaction fees.

Perhaps the most notable sale in the current frenzy was that of paradigm.eth. The address would be a good landing page for Paradigm, the venture-capital fund that recently outraised rival Andreessen Horowitz for the largest crypto fund, a $2.5 billion pool of money it intends to invest in companies that use this technology. But someone else recently bought it for $1.5 million in ethereum, a cryptocurrency that trades for around $4,300. When I reached out to the company about it, Jim Prosser, a spokesman, replied, “¯_(ツ)_/¯.”

Cybersquatting is by no means a new phenomenon. The U.S. passed a law against it in 1999 in the wake of the dot-com version of what’s playing out today, though there are fair-use exceptions for when people aren’t profiting off it or using it as parody. The group behind the domains, Ethereum Name Service, is also against the practice. “We are explicitly anti-squatting, and we have been for years. We think people saying, ‘I’m gonna get the celebrity and brand dot-eth names, and I’m gonna hold out for millions,’ we think that’s dumb,” Brantly Millegan, the director of operations for ENS domains, told Intelligencer. “It’s just extortion — it’s just pure extortion.”

Aside from squatting, the domains’ investors argue, there is much more value to them than just a payout from a company or celebrity. “They’re trying to use domains as a bridge between cryptocurrency wallets and the rest of the internet,” Dr. Milton Mueller, a professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology School of Public Policy and the author of Ruling the Root: Internet Governance and the Taming of Cyberspace, told Intelligencer. The domains are built on ethereum, the second-largest crypto project after bitcoin. Ethereum is many things, but mainly it is a kind of decentralized global computer on a blockchain. In that capacity, it is the most popular platform for various crypto applications, including NFTs and decentralized finance (or DeFi).

Unlike typical website domains, however, ones registered through ENS are not recognized by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, meaning most browsers don’t automatically support the addresses. Rather, they work for cryptocurrency wallets, special websites, and browser extensions. They also come bundled with a smart contract, giving the holder exclusive ownership of the name for a period of time (ENS domains expire but are available for more than 100 years if one is so inclined).

The domains function as a kind of public-facing wallet, a place where you might keep NFTs and cryptocurrencies. But they can also serve as a kind of personal login credential, similar to what many people use Google for on the regular internet. For the people enthusiastically buying and using the domains, it is an early but exciting example of the promise of a new internet — lately, the terms metaverse and Web3 have been catching on to describe this vision — that’s not dominated by tech giants like Facebook. “This is a user name and profile for the internet. There’s no company involved,” Millegan said. “You own your username and account. So that’s one less thing that any service can lock you into.”

Still, for now, the main allure for most buyers appears to be in the quick buck from reselling. The prevalence of the practice has split the community, with some coming out explicitly against it, while others argue that that’s what capitalism is all about. In one case, the decision of whether to squat or not varies for the same person. Will Brown, a Miami lawyer, went out of his way to register the copyright for GeoCities — formerly owned by Yahoo! — as well as to buy the corresponding .eth address with plans to create a community there. But he also registered Draft👑.eth, figuring it probably falls under fair use as long as he doesn’t try to trick people into thinking it’s actually the online-gambling company Draft Kings. “I don’t know of any cases where a company’s gone after their trademark name. I think it would be a novel case,” Brown said. “If they came out and asked me for it, I’d probably give it to them. I own a couple of others that I’ve reached out to companies and tried to give them to them. Nobody’s even accepted.”

[ad_2]