Fashion brands are among those that are being most heavily targeted by cybersquatters, according to a study from the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”). In furtherance of its newly-released report, “Focus on Cybersquatting: Monitoring and Analysis,” the European intellectual property body investigated nearly 1,000 brand-name bearing domains across a number of industries during the first quarter of 2020 – focusing on 20 key brands (which were not specifically named in the report) – in order to identify “suspicious uses of [those brands’] trademarks in registered domain names and analyze the techniques used by cybersquatters to take advantage of” those unaffiliated brands.

Setting the stage in its new report, the EUIPO defines cybersquatting as the “bad faith registration and/or use of another company’s trademark (or another sign that has become a distinctive identifier for that company) in a domain name, without having any legal rights or legitimate interests in that domain name.” In furtherance of this practice, the report states that “cybersquatters exploit the first come, first served principle of the domain name registration system,” thereby, posing “a genuine problem for legitimate brands.”

Defining the domain names as issue as “suspicious,” meaning that the corresponding website was using another party’s “legitimate trademark for non-legitimate use;” legitimately owned/operated either by the trademark holder or with the trademark holder’s authorization; or “unrelated” to the brand in question, the EUIPO found that 49 percent of the sample domains were “suspicious.”

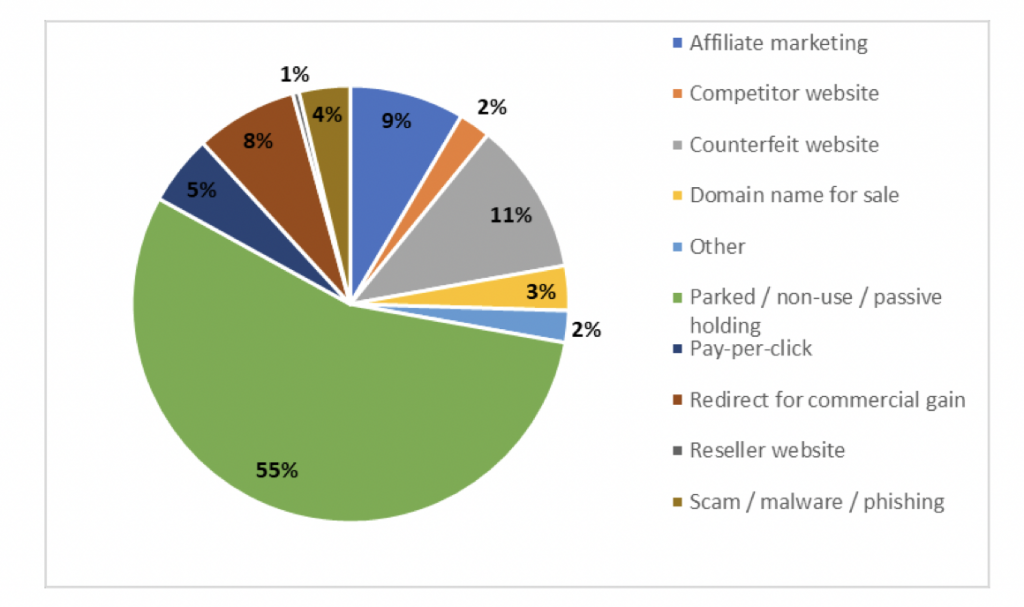

While “not all the domains classified as ‘suspicious’ represented infringements” of the brands’ trademarks, according to the EUIPO, as some of the unaffiliated sites made use of other brands’ trademarks for the purpose of “fan sites or sites devoted to criticism,” for instance, the IP office noted that “a proportion of cybersquatted sites were being used to market counterfeit goods or engage in other illicit activity using the legitimate brand to attract visitors thereby, harming the brand in ways that go beyond counterfeiting.” Among the most common type of suspicious use – 55 percent of the identified domains – came in the form of ones that were parked or subject to “passive holding,” presumably in hope of a sale to the trademark holder, followed by instances in which the infringing domain names were for sale (10 percent).

The rest of the sites “were used for a variety of activities,” according to the EUIPO, with the “most concerning being websites selling counterfeits and websites engaged in scams, phishing, or distribution of malware.”

Breaking down the suspicious domains by “type of name,” the EUIPO found that 85 percent were “regular expressions” (i.e., a domain name containing the trademark within it), while 15 percent were permutations – or in other words, domains that make use of another’s brand name but that include “obvious misspellings, typos (also known as ‘typosquatting’) or domain names with the same or almost identical character in appearance, or different phonetics.” With the latter in mind, the EUIPO noted that “cybersquatters and other infringers do not always register domain names containing the full trademark or brand name, but rather a deliberately confusing variant,” such as a “slight misspelling or replacement of a letter by a digit” in order to avoid detection by the trademark holder.

Looking at the individual industries that were hit the hardest by “suspicious” uses of their trademarks by way of the domain names at issue, the EUIPO found that certain sectors “suffered from significantly above-average levels.” Fashion took the top spot, with 66 percent of the surveyed domains being used for “suspicious” purposes, followed by household appliances (64 percent), and “cars, spare parts and fuels” (60 percent). Meanwhile, 32 percent of the trademark-bearing domains for “brands for regular consumer goods and services” were found to be suspicious, followed by 24 percent of domains for “professional goods and services” companies, with legacy gTLDs (i.e., com, info, net, and org domains) being the most commonly used by bad actors across all industries. (The EUIPO states that the fact that the “new gTLDs accounted for only a small share of suspicious TLDs could simply reflect the low number of such TLDs compared to the legacy TLDs.”)

Specifically addressing its fashion findings, the EUIPO stated that “fashion is one of the most prominent categories in which suspicious activity occurs.” Looking at five different fashion/luxury brands, in particular, the EUIPO found that of the domains identified as suspicious, most of them were registered in 2019, and the countries where the domain names were most registered was the U.S., followed by China, Germany, Panama, and the United Kingdom.

Among its “key findings” across industries, the EUIPO stated that 60 percent of the suspicious domains were linked to websites selling counterfeit goods, and 12 percent were offering up “genuine” – but presumably unauthorized – goods, while 55 percent of the domain names “attracted visitors by projecting legitimacy and 45 percent through both discounts and legitimacy.” Regardless of the purpose of the use of the “suspicious” domains, the report revealed that “every domain redirected traffic from the legitimate brand as part of internet traffic features,” thereby, posing harm to the trademark holder.

Ultimately (and problematically), the EUIPO states that “information about the cybersquatter was not available” for more than half of the suspicious domains, as such information was “marked as ‘redacted for privacy,’ [and thus,] potentially hinders enforcement actions against the registrant.” This could be a “particularly serious issue for small and medium-sized enterprises,” the IP office argues, given that they “often lack the resources to actively monitor their web presence to detect cybersquatting and to protect the reputations of their brands.” And while cybersquatters often target big-name brands, as we reported last year, smaller brands’ trademarks are increasingly being subject to misuse in this way.

Social media traction, innovative products, headline-making fundraising rounds, famous fans, and a creative or charismatic leader regularly prove to be invigorating circumstances that enable young startups to become well-known brands in a shorter time that it may have taken in a less digitally-connected world. With rapid rises to consumer consciousness inevitably comes bad actors looking to bank on the appeal of a buzzy young consumer goods company that has won over consumers across the globe thanks to a must-have product or an effective social media strategy.

Against that background, the longstanding assumption that cybersquatters are only looking to piggyback on the biggest brands – and thus, that only well-established brands like Nike or Gucci need to be aware of the risk of cybersquatting – ignores the fact that it currently takes less time for many brands to differentiate themselves from their competitors, and gain awareness on a large scale, and that this new timetable comes with consequences for young upstarts.